Acupuncture is an alternative medicine that treats patients by insertion and manipulation of needles in the body. Its proponents variously claim that it relieves pain, treats infertility, treats disease, prevents disease, or promotes general health. The earliest written record of acupuncture is found in the Huangdi Neijing ; translated as The Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon), dated approximately 200 BCE. Acupuncture typically incorporates traditional Chinese medicine as an integral part of its practice and theory. However, many practitioners consider 'Traditional Chinese Medicine' (TCM) to narrowly refer to modern mainland Chinese practice. Acupuncture in

The evidence for acupuncture's effectiveness for anything but the relief of some types of pain and nausea has not been established. In the case of nausea, systematic reviews have concluded that stimulation of one particular point (with acupuncture, acupressure and other methods) is as effective as antiemetic medications in the reduction of post-operative nausea and vomiting, relative to a sham treatment. There is evidence that acupuncture can have a small and short-lived effect on some types of pain. However, it has been suggested that the positive results reported for acupuncture can be explained by placebo effect and publication bias. A 2011 review of review articles concluded that, except for neck pain, acupuncture was of doubtful efficacy in the treatment of pain and accompanied by small but serious risks and adverse effects including death, particularly when performed by untrained practitioners. There is general agreement that acupuncture is safe when administered by well-trained practitioners using sterile needles.

Evidence for the treatment of other conditions is equivocal. There is no anatomical or scientific evidence for the existence of qi or meridians, concepts central to acupuncture.

History

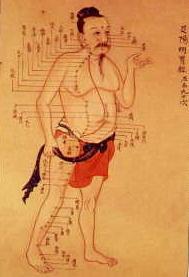

Acupuncture chart from the Ming Dynasty (c. 1368–1644)

Antiquity

The earliest written record of acupuncture is the Chinese text Shiji , English: Records of the Grand Historian) with elaboration of its history in the 2nd century BCE medical text Huangdi Neijing (English: Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon).Acupuncture's origins in

Despite improvements in metallurgy over centuries, it was not until the 2nd century BCE during the Han Dynasty that stone and bone needles were replaced with metal. The earliest records of acupuncture is in the Shiji (in English, Records of the Grand Historian) with references in later medical texts that are equivocal, but could be interpreted as discussing acupuncture. The earliest Chinese medical text to describe acupuncture is the Huangdi Neijing, the legendary Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine (History of Acupuncture) which was compiled around 305–204 BCE.

The Huangdi Neijing does not distinguish between acupuncture and moxibustion and gives the same indication for both treatments. The Mawangdui texts, which also date from the 2nd century BCE (though antedating both the Shiji and Huangdi Neijing), mention the use of pointed stones to open abscesses, and moxibustion but not acupuncture. However, by the 2nd century BCE, acupuncture replaced moxibustion as the primary treatment of systemic conditions.

In

Middle history

Acupuncture chart from Hua Shou (fl. 1340s, Ming Dynasty). This image from Shi si jing fa hui (Expression of the Fourteen Meridians). (

Around ninety works on acupuncture were written in

Portuguese missionaries in the 16th century were among the first to bring reports of acupuncture to the West. Jacob de Bondt, a Dutch surgeon traveling in Asia, described the practice in both

The first European text on acupuncture was written by Willem ten Rhijne, a Dutch physician who studied the practice for two years in

In 1822, an edict from the Chinese Emperor banned the practice and teaching of acupuncture within the Imperial Academy of Medicine outright, as unfit for practice by gentlemen-scholars. At this point, acupuncture was still cited in

Modern era

In the early years after the Chinese Civil War, Chinese Communist Party leaders ridiculed traditional Chinese medicine, including acupuncture, as superstitious, irrational and backward, claiming that it conflicted with the Party's dedication to science as the way of progress. Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong later reversed this position, saying that "Chinese medicine and pharmacology are a great treasure house and efforts should be made to explore them and raise them to a higher level."Acupuncture gained attention in the

The greatest exposure in the West came when New York Times reporter James Reston, who accompanied Nixon during the visit, received acupuncture in China for post-operative pain after undergoing an emergency appendectomy under standard anesthesia.

In 2006, a BBC documentary Alternative Medicine filmed a patient undergoing open heart surgery allegedly under acupuncture-induced anesthesia. It was later revealed that the patient had been given a cocktail of weak anesthetics that in combination could have a much more powerful effect. The program was also criticized for its fanciful interpretation of the results of a brain scanning experiment.

The use of acupuncture as anesthesia for surgery has fallen out of favor with scientifically trained surgeons in

Traditional Chinese Medicine beliefs

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is based on a pre-scientific paradigm of medicine that developed over several thousand years and involves concepts that have no counterpart within contemporary medicine. TCM is based in part on Daoism, with a belief that all parts of the universe are interconnected.Qi, acupuncture meridians and points

According to the Chinese medical classic the Neijing Suwen, disease is believed to be produced by a failure to live in accord with the Dao. Within the more systematized teachings of received Chinese medicine there are endogenous, exogenous and miscellaneous causes of disease. In science-based medicine, disease is attributed to specific (often single) causes, for example bacteria, viruses, or genetic conditions. In contrast to the approach of evidence-based medicine which is based on the germ theory of disease, human anatomy and human physiology, Traditional Chinese Medicine attributes disease and pathology to perturbations in the metaphysical force known as Qi (a word variously translated as "energy", "breath", or "vital energy"'), and imbalance of yin and yang, and the Wu Xing (known as the five phases or elements, earth, water, fire, wood and metal). Qi is believed to flow in and around the body in channels called meridians. Heart-qi is believed to be a force that causes the blood to circulate through the body, whereas in science-based medicine, the blood is propelled by the heart pumping it. Modern practioners may consider qi to be no more than a metaphor for function, but many proponents consider it to be an actual 'substance'. Research on the electrical activity of acupuncture points lacks a standardized methodology and reporting protocols, and is generally of poor quality.

No force corresponding to qi (or yin and yang) has been found in the sciences of physics or human physiology. Support for the existence of qi is often looked for in scientific fields such as bioelectricity but this research is rarely verified and the connection with qi may be spurious.

The location of meridians is said in the Ling Shu to be based on the number of rivers flowing through the ancient Chinese empire, and acupuncture points were originally derived from Chinese astrological calculations, and do not correspond to any anatomical structure. "It is because of the twelve Primary channels that people live, that disease is formed, that people are treated and disease arises." [(Spiritual Axis, chapter 12)].[citation needed] Channel theory reflects the limitations in the level of scientific development at the time of its formation, and therefore reflects the philosophical idealism and metaphysics of its period. That which has continuing clinical value needs to be reexamined through practice and research to determine its true nature.

The anatomical system of TCM divides the body's organs into "hollow" and "solid" organs, for example, the intestines are "hollow", and the heart or liver are "solid". It is believed that solid organs are related, and hollow organs are related, and that there is a balance between the two "systems" of organs which is important to health. The zang systems are associated with the solid yin organs such as the liver, while the fu systems are associated with the hollow yang organs such as the intestines. Health is explained as a state of balance between the yin and yang, with disease ascribed to either of these forces being unbalanced, blocked or stagnant.

It is believed that through birth or early childhood, a “weakness” in one of the five elements develops until it impedes the flow of qi cycling throughout the body, causing the symptoms of illness. Acupuncture is described as manipulating the qi to restore balance. TCM also links the organs of the body to the stars, planets and astrological beliefs to explain the phenomena of the persistence of health and illness in the human body.

Blood

TCM asserts that blood is propelled by qi, that the 100 blood “vessels are the pathways of the blood’, that the vessels gather at a specific acupuncture point (Taiyuan LU-9) associated with the lung (or lungs), and that when qi flow is not in balance, blood pools and stagnates. Modern science-based medicine has shown that blood is propelled by pumping action of the heart, and that there are many more than 100 blood vessels, that the vessels do not gather at that or any specific point, and that blood doesn't fail to circulate except by failure of pumping by the heart, and does not pool or stagnate except when a vessel is physically blocked or the heart pumping is disrupted.Clinical practice

In a modern acupuncture session, an initial consultation is followed by taking the pulse on both arms, and an inspection of the tongue; it is believed that this gives the practitioner a good indication of what is happening inside the body. Classically, in clinical practice, acupuncture is highly individualized and based on philosophy and intuition, and not on controlled scientific research. In the Needles

Acupuncture needles are typically made of stainless steel wire. They are usually disposable, but reusable needles are sometimes used as well, though they must be sterilized between uses. Needles vary in length between 13 to 130 millimetres (0.51 to 5.1 in), with shorter needles used near the face and eyes, and longer needles in more fleshy areas. Needle diameters vary from 0.16 mm (0.006 in) to 0.46 mm (0.018 in), with thicker needles used on more robust patients. Thinner needles may be flexible and require tubes for insertion. The tip of the needle should not be made too sharp to prevent breakage, although blunt needles cause more pain.Both peer-reviewed medical journals, and acupuncture journals reviewed by acupuncturists, have published on the painfulness of acupuncture treatments, in some cases within the context of reporting studies testing acupuncture’s effectiveness. A peer-reviewed medical journal on pain published an article stating that "acupuncture is a painful and unpleasant treatment". There are other cases in which patients have found the insertion of needles in acupuncture too painful to endure. An acupuncture journal, peer-reviewed by acupuncturists, published an article describing insertion of needles in TCM acupuncture and random needling acupuncture as “painful stimulation”. In a peer-reviewed medical journal, one medical scientist published that Japanese acupuncture is “far less painful” than Chinese acupuncture, and that Japanese acupuncture needles are smaller than Chinese acupuncture needles.

Traditional diagnosis

The acupuncturist decides which points to treat by observing and questioning the patient in order to make a diagnosis according to the tradition which he or she utilizes. In TCM, there are four diagnostic methods: inspection, auscultation and olfaction, inquiring, and palpation.- Inspection focuses on the face and particularly on the tongue, including analysis of the tongue size, shape, tension, color and coating, and the absence or presence of teeth marks around the edge.

- Auscultation and olfaction refer, respectively, to listening for particular sounds (such as wheezing) and attending to body odor.

- Inquiring focuses on the "seven inquiries", which are: chills and fever; perspiration; appetite, thirst and taste; defecation and urination; pain; sleep; and menses and leukorrhea.

- Palpation includes feeling the body for tender "ashi" points, and palpation of the left and right radial pulses at two levels of pressure (superficial and deep) and three positions Cun, Guan, Chi (immediately proximal to the wrist crease, and one and two fingers' breadth proximally, usually palpated with the index, middle and ring fingers).

Tongue and pulse

Examination of the tongue and the pulse are among the principal diagnostic methods in traditional Chinese medicine. The surface of the tongue is believed to contain a map of the entire body, and is used to determine acupuncture points to manipulate. For example, teeth marks on one part of the tongue might indicate a problem with the heart, while teeth marks on another part of the tongue might indicate a problem with the liver. TCM diagnosis also involves measuring for three superficial and three deep pulses at different locations on the radial artery of each arm, for a total of twelve pulses that are thought to correspond to twelve internal organs. The pulse is examined for several characteristics including rhythm, strength and volume, and described with terms like "floating, slippery, bolstering-like, feeble, thready and quick", which are used to ascribe a specific imbalance in the body. Learning TCM pulse diagnosis can take several years.Specific conditions

Reproduction

Proponents believe acupuncture can assist with fertility, pregnancy and child birth, attributing various conditions of health and difficulty with the flow of qi through various meridians.A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of in vitro fertilization (IVF), and acupuncture suggests that acupuncture performed near the time of embryo transfer increases the live birth rate, although this effect could be due to the placebo effect and the small number of acceptable trials. A further result of this analysis was that acupuncture during early pregnancy may be harmful.